Irvine Welsh: I don't believe we get rewarded or punished

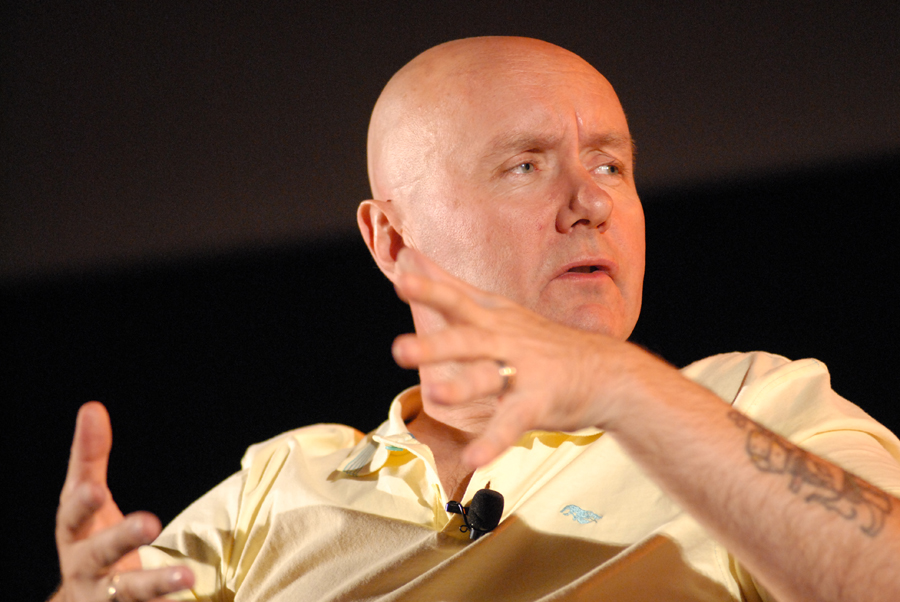

/Irvine Welsh arrives at the Irish Film Institute in Dublin carrying a holdall in two-tone, light beige leather; it gives the impression that he has just walked in from a picnic.

Natural atrium light swamps his head and in a flash he's almost on top of me, swapping his bag from one set of fingers to another and shaking my hand. His face contorts: he is an hour and a bit late and he's sorry.

Unlike many of his fictional alter egos, Irvine Welsh is courteous. Halfway up the stairs to the café's mezzanine level, he's still apologising for his delay, saying something about George Bush being in London, arriving at the airport with helicopters and a cavalcade, while Welsh was stuck in a plane for two hours on the tarmac. Barack Obama is a contender for the American presidency but he thinks John McCain might swing the election.

Blah blah. I'm wondering what's in the bag. Were this one of Welsh's characters, it might be a few rogue kilos of uncut Amazonian cocaine. In fact, it's probably dirty laundry to take home to his wife, Beth Quinn, who lives with him in Dublin. He manoeuvres it carefully under a table. Sounds from the city's Temple Bar district filter through from outside. Welsh's jacket is reversible yellow. His T-shirt, in French, says "What would you do if this was the end of the world?" Well? "I don't know," he says, apparently uninspired by the question he is advertising.

Drugs, as always, run through the veins of Welsh's new book Crime, a story about child abduction and sex abuse in Edinburgh and Miami. Welsh says it's metaphysical. But is it enjoyable? That depends.

Nobody half-likes Irvine Welsh. It's not Lolita nor Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas; nor is it easy to escape the suspicion that certain subjects – rape and paedophilia among them – are so charged, so fat with emotion and meaning, that a writer could piggyback on their shock value should they ever feel that way inclined.

"It's the most difficult thing to write about," says Welsh. "Child sex abuse tests the limits of our liberalism to the full. You have the whole idea of whether rehabilitation is possible or even desirable."

He was about halfway through the first draft when the Madeleine McCann story broke and forced him to stop writing for two months. "I couldn't look at the novel or at the newspapers," he says. "I thought I was never going to finish the book."

The moving, often horrific, accounts he heard from sexual abuse survivors in Miami and Dublin inspired him to continue writing. "You just wouldn't believe some people's stories," he says. "I still can't believe them, that somebody could do those things to someone else."

Welsh talks loudly at times but mostly in mumbly, very quiet, tones. Even in this space without music, surrounded by postcards of Hedy Lamarr, I occasionally find myself lip-reading and missing words. Welsh turns 50 in September; his American wife, Beth Quinn, is 27.

It seems reasonable to assume the couple might want children, and unreasonable that Welsh – in the context of this interview – jokes about men in dirty raincoats. "I think I'm too old now," he says. "If you saw me waiting at the school gates with the kids it would be a case of 999 from the other parents."

He is not parent material, he concludes, and having children would play havoc with his lifestyle. He currently has homes in Dublin, Edinburgh and Miami Beach; he has another in Chicago, where he met Quinn. Most newspaper articles claim she was one of Welsh's students when he taught creative writing in that city, but he dismisses this as an "Eliza Doolittle" fantasy.

"It was in a bar," he says, "where all the best romances happen." The couple married in 2005, and Quinn recently finished a degree in history at University College Dublin.

Welsh says the properties in Chicago and Edinburgh were bought to avoid putting their respective friends and family out whenever the couple visit them. Miami Beach – where Crime was written – is home for the "worst two or three months" of winter, and Dublin for around eight months of the year.

"It's nice," he says. "When you're beginning to piss people off you move, and when you come back again they're pleased to see you." Ongoing stage and screen projects, penned with his long-term screenwriting partner Dean Cavanagh, take Welsh to London on a regular basis, and he is considering moving back to the UK capital.

"Dublin's as good a place as any but I still have a consciousness about Scotland and Britain," he says. "I have an idea that eventually I'll go back but whether I will or not is another question." Remaining in Dublin (he has lived there for four years) would mean getting more involved with the cultural and political life of the city, he thinks.

Leaving would spell the end of the tax breaks he receives as an artist in Ireland, a scheme Welsh considers "welcome but not really fair".

Experience and circumstance have remoulded him, he says, but no more nor less than his peers – friends who have made their money in property, others who have been treading water or gone under. His writing style has developed in that Crime is jammed with descriptions of place and character: the Everglades and highways of Florida are seen with fresh eyes, in contrast to Welsh's self-confessed "over-familiarity" with Edinburgh.

But constants such as football persist. Welsh's team, Hibs, carries such positive connotations in his fiction that, just knowing the new novel's protagonist is a Hearts fan, you worry for the girl he is protecting – a sexually victimised 10-year-old who spends a car journey flicking through her collection of baseball cards.

Welsh says he has become "obsessed" with the American field sport, and prefers it now to football. Or was that soccer? "Football bores the f***ing shit out of me," he says. "I renew my Hibs season ticket every year out of blind loyalty but you know that only one or two teams can win in Scotland. Money has destroyed the idea of the outcome. With baseball, you're in the sun, you get a beer, and it's a very relaxing day. It's not Easter Road in January in the pissing rain."

Welsh has never been afraid of fantasy. Since the publication in 1994 of The Acid House – a collection of short stories in which both God and (the singer) Madonna speak in working-class Edinburgh dialect – he has slipped in and out of the social realism for which Trainspotting was belatedly renowned.

Received coolly at first, his 1993 debut about heroin addicts in the Scottish capital was shoplifted more times than any other book from high street chains. Poor people – the mythical underclass – wanted to read it, and so it must have been realistic.

Welsh recently spotted his most famous novel in an American bookshop under the banner: The Books You Missed At School. "There was The Great Gatsby, The Catcher In The Rye and other seminal American novels," he remembers. "But the only British novel was Trainspotting. I was shocked. It was actually, I suppose, quite an important book, a cultural watershed in a lot of ways. But for your own peace of mind, that's not something you should be thinking about."

Anyone keeping up with Irvine Welsh's recent output might sympathise with the idea that, like Bob Dylan in the 1980s and Woody Allen around now, he is churning words out willy-nilly in a game of ever diminishing returns.

He was laughed out of town by several critics for his last novel, The Bedroom Secrets Of The Master Chefs, and he might get a similar reception for Crime. But it strikes me – after a 10-year gap in reading his books – that his writing is distinctive, even when it comes across as a parody of itself.

This is a world where people look "luxuriantly" at one another and where sordid, chemical-driven sex is a mundane reality. Things start bad, get worse, and get worse again – emotionally illiterate men get bummed by fate in a world of Greco-tragic simplicity.

Welsh's tales, and their disgust quotient, have earned him a persistent reputation as a nihilist, even though that's not how he sees things at all. "I would like to think there was something beyond this life and that there's some point to it all," he says. "I'd like to think there will be some form of reincarnation or rebirth, and that the soul is divisible from the body."

He says he never contemplates such matters, unless a journalist asks him. He has said before that all writers are moralists – "even if they're closet moralists" – which seems more in tune with his general beliefs.

"I think we have a responsibility in this life to do the best we can and be the best people we can possibly be," he says. "I don't believe we get rewarded or punished, but I do believe we have a collective responsibility to try and get the best out of life and make it as comfortable as we can for other people."

His true nihilist period, when "nothing was of any value or use", was the product of his "junkie mindset". He developed and later kicked a heroin habit in the mid 1980s, returning to the drug only briefly while writing Trainspotting.

"It wasn't so much a dabble as a one-off," he says. "I just felt really sick, like I'd never stopped using, so it was a good way for me to sign off." His original habit coincided with the illness and death of his father, a carpet salesman who raised Welsh, with his mother, in Leith and Muirhouse.

"My response to his death was quite a traumatic thing for me and I didn't handle it as well as I could have," he says. "I think my drug problem was a form of denial that he was ill and dying. He actually should have died earlier but he pulled through and came out of a coma. I'd almost had this belief that he was indestructible. He would have been about the same age as I am now."

Welsh used to think he would never reach 30, let alone 50. He has stopped taking drugs "to any great extent" and prefers the cardiovascular highs of boxing and running. He says he is getting sportier the older he gets, and now supplements activities like horse riding with reading the novels of Jane Austen, whose density and complexity he loves.

The ever-increasing severity of comedowns, and the "ennui" of yet another binge, have conspired to refocus his mind. But not those of his principal characters. Welsh recently described himself as "not so much middle-class as upper-class" but still feels compelled to write morality tales wrapped in chip paper, often breezily defiant in the face of the questions they are posing.

He is the delinquent cousin of Burns and James Hogg, his books The Private Memoirs And Confessions Of A Justified Sinner in a world where sin is passé. "It's weird," Welsh says. "I write all this bleak, urban, edgy fiction but I'm reasonably happy. The real miserable fuckers are the people who write beautiful poetry. I'm sure there's no empirical basis for saying something like that other than my own prejudices, but I'm quite happy with my own prejudices."

Of the films he is currently working on, The Meat Trade is the closest to starting production. Starring Robert Carlyle, Colin Firth, Samantha Morton and, oddly, Razorlight's Johnny Borrell, it will tell the story of 19th century body snatchers Burke and Hare in a contemporary Edinburgh setting.

Welsh enjoys the social side of working on films but, when those projects stall, he returns to writing novels in Miami. His next book, after a new collection of short stories in 2009, will be a Trainspotting prequel, culled from the 250,000 words of manuscript used to furnish the original 100,000-word novel, explaining the main characters' descent into squalor and dependency. Though a big part of Welsh's past, Trainspotting seems incongruous with his present lifestyle.

The story comes to mind of the drug-addled, wife-shooting William Burroughs, the American junkie celebrity who lived in Morocco for many years, and for whom Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac rescued type-written, blood-stained pages from the floor to shape randomly into The Naked Lunch.

But then I'm back with Irvine Welsh and his holdall of imaginary cocaine. He's scanning the manuscript for the Trainspotting prequel onto his computer at home, he says, and it dawns on me why this is making me sad. There will always be artists, like Burroughs, whose fascinating lives are rendered imperfectly in tortured prose. With Welsh, as with Quentin Tarantino, the worry is that he keeps gambling on genres that worked before and maybe one day will again.

"I don't sit down with the game plan of writing in any particular genre," he counters. "I just write." He used to fantasise about buying a pub in Greece and being the "big, fat, ex-pat landlord" but the reality of this – now that he can afford it – doesn't appeal.

"What would I do if I didn't write? I couldn't just sit and watch telly or go down to the pub all day – I'd get fed up with that really quickly." If he lived to be 500, he says, he would still have fresh topics to write about.

"I'm not saying the books would be any good but there's never a shortage of material." He would continue to be as prolific, as self-deprecating. Crime's ending was written, he says, with his readers in mind, as a reward for "going through all this stuff"; in the book's afterword he thanks everybody who has ever slagged him off "for taking the time to care".

Outside, and on the phone to Quinn, he is apologising once more for running late. An Edinburgh man recognises him and starts shouting that it's Irvine Welsh. He can't believe it because he saw Billy Connolly, right here in Dublin, the night before.

The excitable man would give the author a high five and a cuddle if he could. But Welsh gives a friendly thumbs-up, lifts his bag of dirty washing and slinks back into Temple Bar.

First published in The Sunday Herald, 2008.