Vipassana meditation: keep calm and carry gum

/The concept of Noble Silence is fundamental to Vipassana meditation. You don’t talk to anyone for the duration of your stay; you don’t make eye contact; you refrain from singing show tunes in the shower.

By extension, no-one talks or makes eye contact with you. I’ve been to parties in Edinburgh like this, so have no objections in principle.

But this time was different. After being told about the facilities, and reminded we couldn’t leave the site for the next four days, Noble Silence descended. That was in the kitchen block at 7.50pm on Thursday, 10 minutes before the first sitting.

At 7.53pm, in my dorm, I realised I’d left my toothbrush at home. I realised this with my hand, inside my backpack, groping frantically. I had the paste but not the brush.

I rummaged through the bag again. And again. Socks. Panties. But no brush. I drew the curtain across my cubicle and considered suicide. Then I bit my clenched fist, shook it at the gods and mouthed the word Scheiße several times.

My mute dorm-buddies made haste arranging their sleeping bags, toiletries, crack pipes … and there was I, Mr No Brush, twisting in the wind of Woori Yallock.

I sat on the slats of my rudimentary bed, looked at the bare plywood walls, feeling like a prisoner of war …

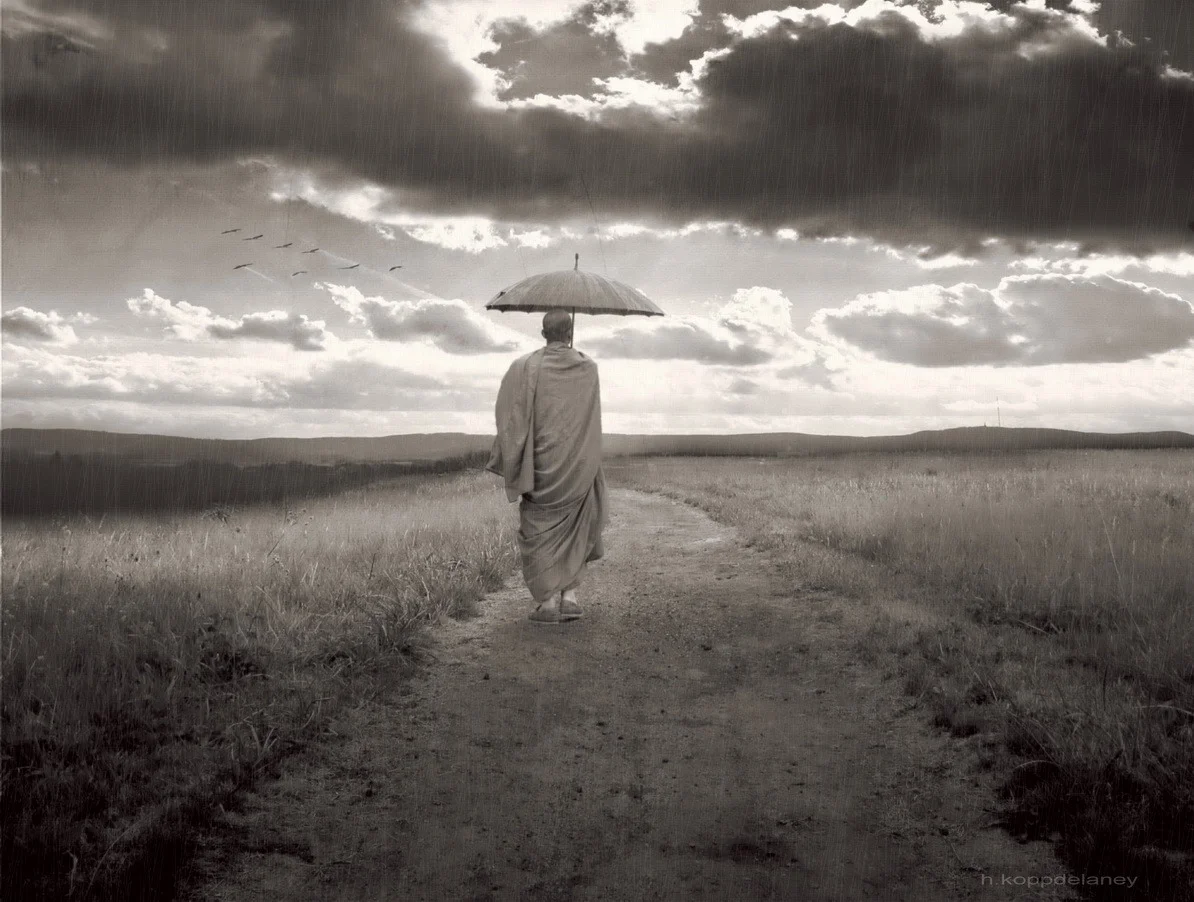

In the meditation hall, I crossed my legs, wrapped a woolly blanket round my shoulders, back and legs.

Sadly, we didn’t get to see Goenka on VHS, but I was happy to hear him on cassette after three and a half years.

He was the same old Goenka: equanimous as anything, enlightened as bits.

Learn to master your mind, one debilitating leg cramp at a time.

It takes a while to get into it, of course. You breathe in, breathe out, think about your toothbrush, your teeth, your frigging toothbrush …

I would survive the night, but would I make it to Sunday evening? My poor gnashers: I wouldn’t have blamed them if they jumped ship.

I tried controlling my faculties, reminding myself it’s all impermanent, annica, annica … that sensations arise, pass away …

It was Baltic outside the meditation hall – a full moon, clear sky. In the sleeping quarters, the warm smell of my dorm-buddies’ bodies was repulsive and weirdly welcoming.

I thought of the men in Stalag Luft III and other containment camps … my brothers.

In the bathroom unit, I claimed one of four sinks, then sooked a fat blob of Colgate from the tube and tried to swill with it.

This required considerable oral oomph. It was tart; my eyes streamed a beauty.

Passingly satisfied with the fluoride coating, I used my index and middle fingers as a brush.

It was rubbish.

The prisoners at the other sinks brushed as if they’re lives depended on it. One guy in particular thrashed his molars, working up a lather, purging the surface of his tongue.

I watched this in my peripheral vision, while pretending not to, which meant my fellow PoW’s could probably see me too. But as I gagged, I knew we were all gagged: I couldn’t ask for help and they couldn’t slag me off.

Someone banged a gong at 4am on Friday for the first meditation of the day.

It started well. I got some good Anapana in, some decent chill.

We had to focus exclusively on the breath lapping against our philtrums; but in time my gob started mouthing off in my mind’s eye.

I once asked my dentist, post scraping, how long it would take for new plaque to form.

“Hahahahahahahah,” he said, darting a glance at his female assistant, who in retrospect he was probably banging.

“Oh Paul,” he said. “Hahahaha. It’s started already.”

I replayed this scene against the back of my eyelids a few times. It was 18 hours since my last brush, 54 or so to the next one.

My philtrum twitched.

Day one’s objective was simply still the mind. Have you ever stilled the mind? It’s not simple.

You think you’re getting there, but no – off it goes, for a minute, an hour, a month …

As the cranium quietens, you start seeing how these distractions and reactions form. For me, one went something like this:

I felt my shoulders loosening …

… saw a thread getting caught on clothing, drawing the fabric together in tight, little waves …

… thought this was a good analogy for my relaxing shoulders …

… recalled how satisfying it is when you pull the fabric and it straightens out …

… wondered how I’d put that feeling into words …

… convinced myself this thread-catching happens only in nylon …

… pondered the production and use of synthetic polymers …

… got a sudden mental image of my gran’s navy nylon trousers …

… remembered she had passed away …

… started crying.

It’s true what Moses said: the brain’s a mental organ.

By Friday evening my mouth was a festering moth. I could use a sock to clean my teeth, I thought, a T-shirt but, no …

Escape was an option, however remote. Had I not seen, just that morning, two burly laundry men picking up adult-sized bags of linen and throwing them with abandon into a laundry truck? No, I hadn’t.

Ultimately, you’re responsible for your own liberation.

There was plenty of plywood to shore up a tunnel. I could shake earth from my pajama bottoms before the next sitting.

After my last Vipassana course, I was told someone had tried escaping in the dead of night and was “persuaded” to stay – i.e. caught in the carpark and beaten to a meditative pulp by the volunteer management.

How many others have simply disappeared, “become enlightened”, “transcended”?

Naturally, I’d given the site a pretty good recce in my spare time.

A few acres, fenced in; trees around the perimeter; fields stretching to the horizon across the Yarra Valley. If they sent the rottweilers after me I’d be dead in no time.

Under cover of darkness, I kicked some stones about, edged closer to the site carpark.

There were no guntowers as such, but structures either side of the gate: one was disguised as a prefabricated hut, the other as a moss-laden caravan. If I could make it to the car, anything was possible.

I knew there was a Coles supermarket about three miles east, full of brushes – a hair brush would do, a broom, a lint remover.

When the pre-dawn gong went on Saturday, I squeezed more Colgate into my moosh.

Meditation halls the world over are dark and cold at this time of day, which makes it hard to see people sitting there. You knee them in the head as you pass, and can’t even apologise.

You have to get to your cushion, get your blanket on, your hoodie up, yawn, crack your knuckles, scratch your nuts.

My brain was still engaged with Goenka’s free-ranging discourse from the night before.

Goenka: Observe your sensations …

Brain: Gum disease, swollen tongue …

Goenka: Let go of attachments …

Brain: A brush, a brush, a brush …

Goenka: Focus on your breath …

Brain: Erm …

Goenka: Be happy …

Brain: I can’t …

Each time my tongue tapped furry enamel my desire to escape intensified. At several points my mutinous mind wandered out to the tea tree forest on the site’s western perimeter.

I’d sneaked into it the day before, and cut a path through the trees until seeing signs warning me not to go any further.

I’d stood there for an hour and a half singing Leonard Cohen songs.

The signs were alluding to the fact there was, just a few steps away, a sheer drop to near-certain death down a treacherous gully.

But if I survived I could be up to the supermarket and back in an hour, provided my ankles weren’t broken, the gashes in my bonce not too severe.

I’m doing it, I thought, still sitting, knees blow-torch burning – I’m escaping.

No, yes, no, yes, no …

The clunk of the penny dropping, that I’d given the course manager my wallet and phone for “safe keeping”, wasn’t pleasant. It knocked the wind from my sails.

Even if I survived the fall, fought off rabid wallabies and made it into Coles in blood-stained pajama bottoms with bad hair and feral mouth, what was I going to do? Ask them to give me a toothbrush for free? Steal one?

I denied myself honey in my ginger tea for the third night in a row on Saturday … Mr McCavity said no in no uncertain terms.

This bugged me. This bugged me a lot. The drink was the only sustenance permitted between 11.30am and 8.30am the next morning.

That did it. I cracked.

I left the kitchen block and bumbled cautiously though the darkness, arms outstretched. I crossed some rough terrain en route to the course manager’s accomodation.

I climbed some steps. Faint light escaped through a gap in his curtains.

When he opened the door we made eye contact, and I laid the whole thing out straight/ slightly sheepishly:

“A problem … I’ve got a big problem … My teeth … haven’t brushed them … my gums hurt … I need a brush …”

The course manager nodded and bowed slightly. “We sell brushes here on site,” he said. “If you come with me, I’ll get you one.

First published on Innocent in Australia, 2011.