Jon Cattapan interview: a portrait of the artist as a new director

/As he begins a new role at the Victorian College of the Arts, Jon Cattapan talks life, loss and longevity in one of his most cherished places: his studio.

By Paul Dalgarno

Jon Cattapan parks his car, grabs his keys. We’re in an industrial estate in Moorabbin, a 40-minute drive south from the Victorian College of the Arts, where Cattapan was recently appointed Director.

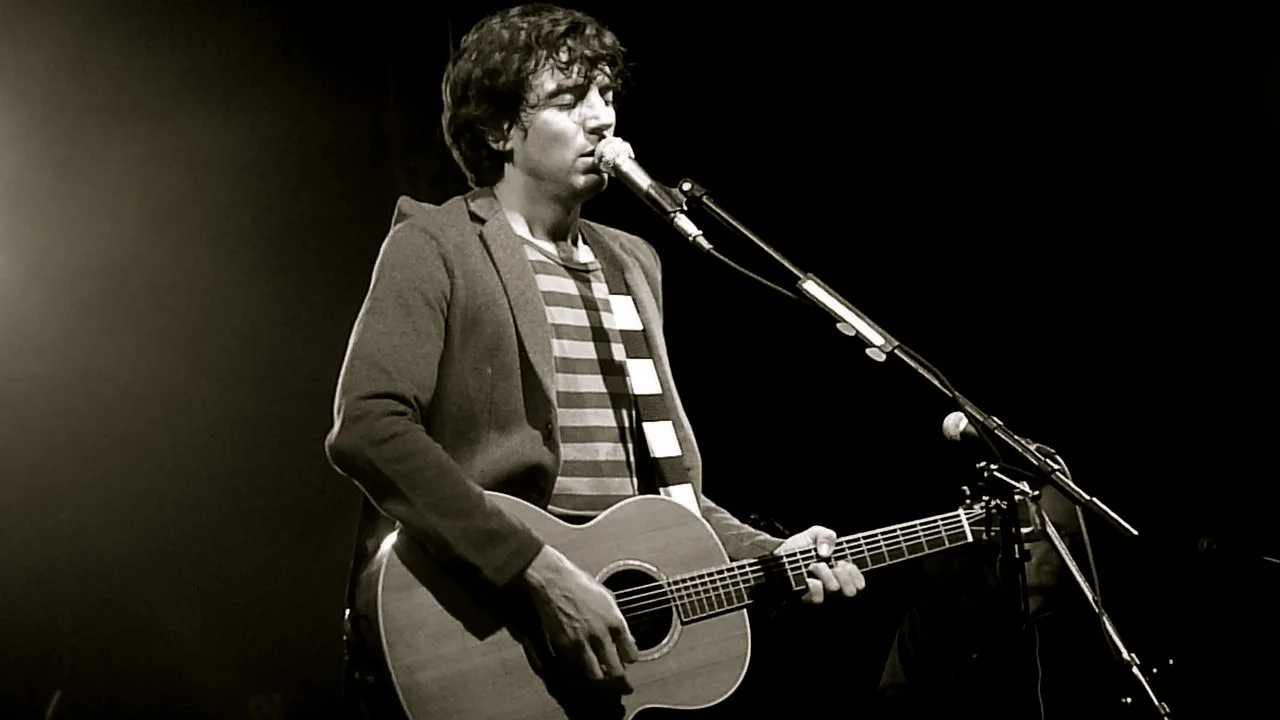

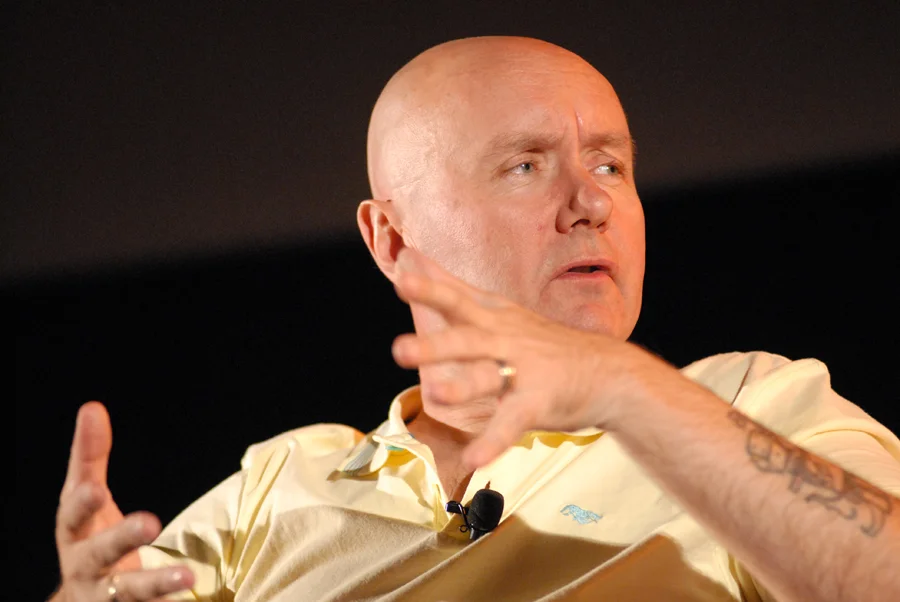

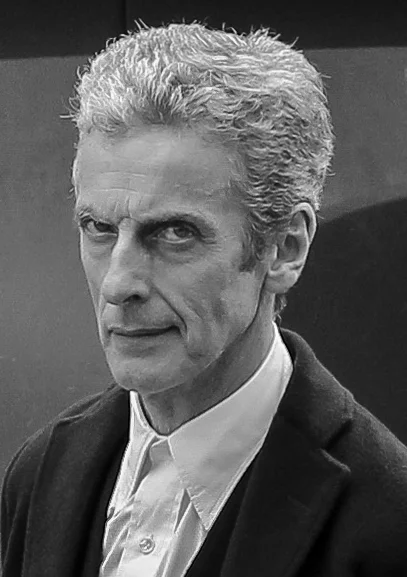

VCA Director Professor Jon Cattapan. Photo: Giulia McGauran.

There are forklifts, corrugated iron doors, some open, some closed. If I didn’t know better, the inconspicuous-looking door Cattapan gets his key into might lead to a nut-storage facility, a spare-parts outlet.

“Here we are,” he says, pushing open the door, gesturing. “My sanctuary.” Inside it looks two-parts Tardis, one part paint-ball site. Spattered tarps, tins and tubes of paint. Large-scale finished and in-progress artworks in deep and lucid greens, in cream and off-white, burst forth from the concrete walls, the concrete floor. The skylights – two strips of corrugated plastic running the length of the studio – are dirty, softening the light.

Grey Nocturnae (the Pool). 1996–1999. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

At the far end, storage racks on two levels, teeming with work; to the right of those, a sink and kitchen area; above us, a mezzanine level, closed off, with curtains. Next to me a piano; next to that a left-handed acoustic guitar. Cattapan studied classical guitar in the past, was in bands during art school, and now plays as a means of transportation.

“I'll often come in here and strum for half an hour while looking at my work,” he says. “It’s my bridge between the real world and here.”

He puts on the kettle while I look around for clues to who he is. Because I work at the VCA, I see Cattapan fairly regularly, but never with dirty hands or overalls. When I started working at the College in 2016 he was Deputy Director, a position he held for two years. I knew he had work in Australian State museums and regional galleries.

I knew he’d been deployed to Timor Leste as an Official Australian War Artist in 2008. I knew he’d won the $80,000 Bulgari award in 2013 through the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and that his work had adorned a tramduring the Melbourne Festival in 2016. I didn’t know how he coped with the daily flip-flop between senior academic and practising artist.

“Look, it's challenging,” he says, sitting in front of me, tea in hand. “Maybe it would be a lot easier if I had a studio closer to the VCA. When I took on this new role I toyed with the idea of using my old VCA office as a studio. But I actually think it's better to have that separation. In the half-an-hour or so it takes me to drive to the VCA I've got enough decompression time to get my head into real-world mode. I love to be in my own head, but I'm aware there are lots of people counting on my decisions.”

The City Submerged No 21 (detail). 1991–2005. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Does he have a vision for his time as Director? “I’d like to think that within my three-year year contract we’ll have undertaken a full regeneration of key staff,” he says. “I’d like to think our new facilities are bedded down and working well. I’d like to think the institution itself, the way we work within it and sell it to the outside world, is much more porous.”

He’d also like to see an adjustment to the College’s ethos. “The VCA is still, rightly, very much about the purer end of art – what we might call research, and that's great, but I think there's also a place for the applied aspects, and commercial possibilities. I think a bit of a bit of tension between the pure and applied art forms could, and should, be harnessed very positively.”

Turning. 2002. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

In terms of his own creative energy, he’s currently pulling together works for three upcoming shows and, while his natural inclination in the studio is to “mooch around for a while, maybe even days, just looking and thinking,” that’s not currently possible. Finding time to create meaningful work – and come to terms with the failures – is hard.

“I’m not necessarily the best judge of my work, and I work out of doubt” he says. “But you get an intuitive sense when you've done something that excites you. In my case, that might not be an entire painting. I might have done a mark or a dribble and thought, ‘Well, that's different, where did that come from?’”

For all their variation, the works in his studio could only be Cattapans: colour-popping canvases overlaid with dots and lines suggesting codes, maps and data; a meshed layering of a cityscape; night-vision greens, punctuation-point reds, layered figures.

Raft City No 1 (Surveillance Version). 2015. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Does being successful and known for a particular aesthetic make it easier or harder to make new work? “It’s difficult for me to work with a clean slate given my first show was in 1978,” he says. “But you still have to be prepared to step outside of yourself, to keep testing yourself to see what else is there, to fail a bit.”

The studio is walking distance to Cattapan’s childhood home. His parents emigrated to Australia from Castelfranco, Italy, in the 1940s, the famed birthplace of the 15th-century painter Giorgione. They found themselves in Carlton, and then Highett which, when Cattapan first lived there, had “dirt roads, open drains, no sewage system”.

The youngest – “by far” – of four children, he describes himself as “the classic Catholic mistake”. In his early years he spoke Italian at home with his parents, English with his older siblings. When he was six his mother took him to Italy for six months, where an older cousin taught him to draw and saw some potential.

Rib City. 2007. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

On returning to his Catholic primary school in Melbourne, others saw it, too. “The nuns all thought I'd been touched by the hand, so to speak, and I decided not to argue,” he says. “From that point, it felt like a pretty natural thing to mess around with – drawing and trying to paint and so on.

“At 15, I met an extraordinary young high school art teacher, Ralph Farmer, who changed my life. He turned me on to what a life in art could look like, and I'll be forever grateful. He’s the reason I ended up teaching, actually. I always thought it was such a great act of generosity, that if I could find a kid like myself to help then I would.”

Farmer had a hand in encouraging Cattapan to switch from the RMIT computer science degree he'd enrolled in in 1974 to the RMIT School of Art instead, which at the time was staffed by artists such as Andrew Sibley, Jan Senbergs, George Baldessin and Les Kossatz.

“Ralph suggested just testing it out for a year,” says Cattapan. “But I took to it like a duck to water. It felt absolutely like I’d found my tribe.”

Documentary (Melbourne as Rome). 1989. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

It’s a regret for Cattapan that Farmer, who died at a young age from a brain tumour, didn’t get to see what Cattapan would achieve with his art. An unlucky break for the man he describes as his first lucky break.

“You need a lot of those lucky breaks to be a long-term artist,” he says. “One has to work very hard of course, and hopefully one is sincere. But those things pale somewhat against the idea of coming across the right inspiration at the right time, or finding the right materials or technology, or whatever it is that can really take your work forward privately and then publicly.”

Does he think things are easier or harder for young artists now?

“I do think our generation had it easier in some ways, for the simple reason that you could find a studio space in Melbourne much more easily,” he says. “I'm not surprised to hear younger artists are moving out to regional areas. When I was starting out you either had to be in Melbourne or Sydney, but that’s definitely changing – it's way too expensive now.”

Jon Cattapan’s Melbourne Art Tram. 2016. Image courtesy of Melbourne Festival and Yarra Trams.

Each generation, he says, becomes adept at finding its own solutions, but only the best artists go the distance. “A lot of people drop away because of misfortune or misjudgement. Some careers can take off quickly. But over a longer period, as people rise, fall, rise, fall, you notice that the best people keep just simply keep making.”

In his own case, his chosen medium caught a lucky break. By the early 1980s, painting, which had been anathema to young artists for years, was back in vogue, regaining lost ground from sculpture, performance art and early video work.

“Galleries were suddenly very comfortable with painting because they actually had something to sell again,” he says. “By 1983, I’d joined a very reputable gallery in Melbourne, Realites Gallery, and the first show I had with them was almost a sell-out. The works were cheap – it wasn't like I could live off the proceeds, but it gave me a sense that something had really shifted. I began to feel more comfortable about introducing myself as an artist.”

Dark Eternity. 2016. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Place has long been a constant in Cattapan’s work, the way it’s interpreted and used, the shared experience of urban centres, the places that – while still recognisable – have been dulled by homogenisation, the places that accommodate, or even punish, the displaced.

He credits that interest to Giorgione and a family tragedy. “There are two major works of his I'm interested in,” he says. “The Castelfranco Madonna, and The Tempest. In both, you can see Castelfranco in the background and, for some reason, I kept coming back to that idea, the representation of place in the background, and it started to really take hold.”

That was in 1985, when Cattapan was 29. He’d gone to Italy with his girlfriend and three other Australians to “zone out” for six months following the death of his sister, Adriana. “I felt then I’d maybe done my work as an artist,” he says. “I'd been acquired by museums, I'd had reasonable critical success with solo shows, I’d had a career of sorts. I thought maybe there was other stuff I could do.”

Sister. 1984. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Was that a grief response? “Yeah, absolutely,” he says. “I was depressed. My sister didn’t have an easy life – she was a fairly helpless person. It was a very complex psychological situation of the sort that can happen when someone very close to you dies. You think of all the stuff you fret about as a younger artist – ‘Is my work ever going to find its place?’ ‘Is there anything original about it?’ ‘Is this or that curator interested?’ – and none of it seems important any more. The personal family stuff just really took over for a while.”

Name and Address (1988). Jon Cattapan.

Back in Melbourne, he thought about artists such as Arthur Boyd and Sidney Nolan, and their use of St Kilda – where Cattapan has spent most of his adult life – as a backdrop. “I thought, ‘Huh, you know, Giorgione and Castelfranco, Cattapan and St Kilda, I could do something with that’.”

He made paintings featuring night visions of St Kilda, reflecting the “nocturnal street-workers and drugs scenario of the mid- to late-80s", such as Name and Address and A View From Flat 3/42 Grey St.

A View From Flat 3/42 Grey Street. 1987. Jon Cattapan. Image Courtesy of the artist.

He has since lived and worked in the UK, Europe, India, South Korea and America. He upped sticks for New York in 1989, moving away from the fascination with St Kilda to the broader idea of the urban environment. He shot thousands of photos in New York, felt overwhelmed. “I thought it was going to be perfect but in actual fact the poetry of the street-scape was too much to handle,” he says. “I ended up making completely blank, abstract works, like The Blessed Virgin and Dog Day (Seep).”

The Blessed Virgin. 1991. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

His residency at the Canberra School of Art in 1991 morphed into a teaching post in computer-aided drawing, an area that was still in its infancy. His practice these days often starts with a scanned image, which is then reworked and rearranged before being transferred onto the canvas and added to, layer by layer. He has the Canberra job to thank for that.

“I began to think about the photos I’d taken in New York, and then layers of pictures, and then layers of information,” he says. “I remember printing one out, which became a painting called The Book Builder. As soon as I saw it I thought, ‘I know what to do now – it fed me for a very, very long time’.”

The Bookbuilder. 1992–1993. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the early 2000s his works became less abstract, more politically engaged, and the human figure returned. “I was particularly incensed, and still am, about the terrible treatment of asylum seekers in Australia,” he says. Human cargo became a theme, as did refugees – and, from that, another lucky break.”

Carrying. 2002. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

He was appointed as Australia's 63rd war artist in 2008, although he has written elsewhere that the term “war artist” seemed too dramatic. “I joined a peace-keeping force in Timor Leste and, while there was ever-present security and intelligence-gathering, the country was relatively stable. It was, as they say in the army, ‘low-tempo’.”

But his experience there led to a huge body of work – and continues to influence his practice. He would follow the soldiers out on night patrol and shoot photographs through a night-vision monocle, resulting in luminous and unearthly images that translated to works such as Night Figures (Gleno) and countless others since.

Night Figures (Gleno). 2009. Jon Cattapan. Image courtesy of the artist.

Looking back over his career, although his style and approach have changed, Cattapan sees a “continuum of ideas”, and I get the sense this through-line matters to him. “I'm hoping that people understand when I've shuffled off this mortal coil that there was this guy interested in this particular set of ideas and in exploring them through paint.”

Jon Cattapan in his Melbourne studio. By Giulia McGauran.

I know, without looking, that our time is nearly up, that Cattapan will soon stand and start morphing back into the Director of the VCA. But then he’s just mentioned mortality, and I want to know what he thinks happens when the mortal coil’s been shuffled.

“Are you talking about the spiritual realm or what happens to your work?”

“Oh, the spiritual realm,” I say.

He grimaces slightly, considers the question, smiles. “I’d like to think there's something out there for us. Having grown up Catholic, it's pretty hard to let go of the idea that there's an afterlife. In my wilder moments, I'd like to think my favourite artists will be there to meet me, pat me on the head and say, ‘Not bad. You had a few wins. You could have done better, but you did okay’.”

First published on the University of Melbourne's ART150 website.