Peter Capaldi: you're just a journalist

/stemoc/wikimedia commons

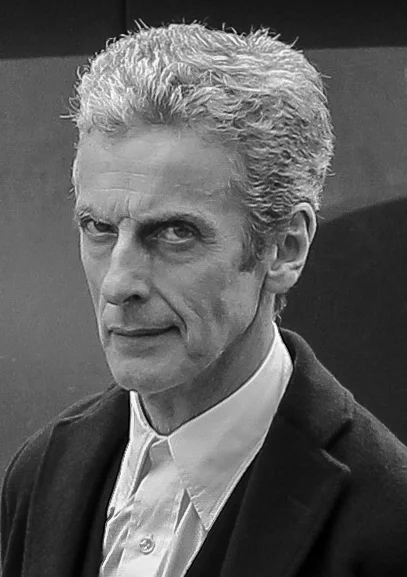

Peter Capaldi, the Scottish Oscar-winner, is about to blow, but not quite yet. His cropped and grey-flecked hair is getting closer to his eyebrows, but only because those eyebrows are raising sharply – the left one, in particular, arcs like a hieroglyph over his steely left eye.

He rubs his mouth, near seething, as if to hold the venom inside, and veins strain noticeably in his neck. "You've got to fucking do things my way, whether you like it or not," he says.

"You're just a journalist from the Sunday fucking Herald and I'm not interested in your opinions, OK? So just fucking listen or you will not talk to me, or have access to my people, as long as you fucking live."

Capaldi settles back in his seat, spent. He has a habit of slipping unannounced into the body of Malcolm Tucker, the foul-mouthed spin doctor he has made his own in the cult political satire The Thick Of It.

It's a little scary to be on the receiving end, even though he's just pretending, but he says he needs lots of practice. A full-length movie of the series is about to start filming. It will be set largely in Washington and placed loosely, but recognisably, in the context of the Iraq war.

The bile Capaldi brings to the role is born of past experience, dredged up and sieved into concentrated form, remoulded and transmitted like a virus through Tucker's pores.

Look at the highlights of Capaldi's career and you'd be pushed to find reasons for this anger: his breakthrough as Danny Oldsen in Local Hero in 1983, the Academy Award in 1993 for his short film Franz Kafka's It's A Wonderful Life, his fame, since 2005, as an Alastair Campbell-style attack dog in The Thick Of It.

But it's the decades in between, full as they have been with television roles, directing projects and bit parts in movies, that tell the real story. Not low points as such but ...

"Troughs" he says, unleashing an infectious and rattling laugh, his eyes tightly closed, his head tilting back. The real Peter Capaldi has returned, fully affable. When he laughs, it's hard not to get swept along, although it's not really clear why we are laughing.

"It's been great," he says. "I was at the Baftas two years ago for the first time in ages and bumped into a friend I'd worked with a very long time ago. He grabbed me and said, We're still here, mate' and that's true, we're still here. It's a great profession to be in, and to have survived in for so long."

He looks at the clock on his mobile phone, as if his life might be marked out digitally. But mere survival is not necessarily enough, he says, not quite the fulfilment of his life's acting ambitions. He turns 50 next week – a bugbear but no real biggy.

"It's OK," he says. "But I wish I was 40. My father died a couple of years ago and at my age that starts happening to a lot of your peers and friends so you become more conscious of the ever-darkening shadow. But that's fine, it sort of propels you into doing more. Both myself and my wife are actually busier than we've ever been and that's a fantastic place to be."

His wife, Elaine Collins, was also an actor and now develops programmes for ITV, which provides Capaldi with an alternative view of his profession. Their 15-year-old daughter, Cissy, has no ambition to follow in their acting footsteps, a decision that cheers Capaldi no end, even though he's not lacking offers of work.

After The Thick Of It movie – provisionally called In The Loop – he will start filming another series of the show for BBC Two. He is currently having a prosthetic head made for The Devil's Whore, a forthcoming mini-series in which he will play Charles I in the weeks leading up to his execution.

Later this month he will guest star in Doctor Who as Caecillius, a marble dealer from Pompeii, who befriends the doctor and his new assistant.

Touching the Tardis was a dream, a flashback to the Jon Pertwee era of the show and his own childhood. "When I was a kid I wrote to the BBC and the producers sent me a huge package through the post with Doctor Who scripts," he remembers. "I'd never even seen a script and couldn't believe that they actually wrote this stuff down. It sort of opened a door."

Until that point, doors had led in and out of rundown Glasgow tenement blocks in Keppochhill Road, Springburn, where the Capaldis and their relatives lived. On one side of the road – "the tough side" – were his mother's family, who came from Killyshandra in Ireland's County Cavan; on the other side was his father's family, who came originally from the hillside village of Picinisco in central Italy.

Capaldi only recently discovered that The Thick Of It writer and director Armando Iannucci was raised in the same street and that their parents had once been friends.

The one time he visited Picinisco, he was struck by a war memorial in the main plaza with surnames he recognised from Glasgow fish and chip shops, hairdressers and ice-cream parlours. His own family's exodus began with his grandfather, one of seven brothers who went to America and lost a leg building the Brooklyn Bridge, before ending up, after stints in Newcastle and Liverpool, finding work in a Glasgow café. Or at least that's the myth.

"It's hard because people tell you things, but the more I think of it now, the more I think they just made it up," he says. "In those days people could just disappear, and maybe they went to prison. For all I know, my grandfather was a bank robber in Kilsyth. But I always thought it was funny that my grandparents had bought a ticket to New York and ended up in Glasgow."

Capaldi's father drove an ice-cream van, selling the gelati he made in a makeshift factory not far from the Keppochhill tenements. The family wanted to point the young Capaldi in a different direction – one that would eventually lead to him studying illustration at Glasgow School of Art, where he also enjoyed a stint as the frontman in a punk band called The Dreamboys.

"There were always pens to draw with, or a piano if you wanted to learn music," he says. "My grandmother used to say it was an Italian thing, that all the great artists came from Italy. She somehow felt it was appropriate to encourage that in me, although I don't think it was ever thought about consciously."

He had already tried and failed to gain a place at a London drama school when he got his big break opposite Burt Lancaster in Bill Forsyth's film Local Hero. The director had been visiting Capaldi's landlady, a costume designer, when the 25-year-old art student stumbled into his life. "I was just renting a room," says Capaldi.

"They had worked together before on a one-off BBC Scotland film called Andrina. I came home one night the worse for wear and my landlady introduced me to Bill. I was intoxicated but also reasonably amusing." Quarter of a century later, he is still recognised for his part in the film, and particularly by fans in America.

"They're an odd race," he says. "The ones who love that film seem to watch it five times a year or more." The decade that followed the film's release was spent in London bedsits mostly, doing repertory theatre, and feeling nervous and unsure of his abilities.

His past resurfaced in his 1992 screenwriting debut, Soft Top Hard Shoulder, a film in which he starred with his wife, playing an arty and largely disinterested heir to a Scots-Italian ice-cream dynasty. An ice-cream van pops up again briefly in the commercially unsuccessful Strictly Sinatra, a Glasgow gangster film he wrote and directed in 2001, and which starred Ian Hart and Kelly Macdonald.

He takes ultimate responsibility for the film's failure, citing his own directorial inexperience and a series of crippling hitches. The title had originally been Saracen Street, and its replacement still makes him cringe. "Nobody would give me any money unless I made compromises and in the end there were too many," he says.

"The producers only liked half of the film and I just thought, Fuck it – half a film is better than nothing'." Unsurprisingly, the end result was uneven, and Capaldi went into meltdown. "I should have just gone and done something else, but being Scottish, I wore black and went into mourning for five years. I decided that was my comfort zone, which was crap. But then, looking back, it was a tremendously educational experience."

Eight years earlier, in 1993, he faced another stiff learning experience. The Oscar success of Franz Kafka's It's A Wonderful Life set Hollywood execs on a charm offensive. Bob Weinstein of Miramax snapped up the rights to a feature-length film script Capaldi had written and even Kafka would have been pleased with the plot turns that followed.

"We developed the script for about a year and a half and then they said they were going to make the film," he remembers. "I immediately flew to New York to start putting the production together but while I was in the air they changed their minds. When I got to the office they said, We're not going to do this any more. Here's a plane ticket. Off you go.' By that time it was more than a year since the Oscar win and nobody wanted to know me."

Cue a familiar sensation of uncertainty and self-doubt. He was inadequately prepared to deal with fame, he says, to take advantage of opportunities when they came his way, to forge ahead when things looked bad. "I would go into rehearsal rooms where people had been to RADA or Oxford and just tug my forelock," he says.

"My parents didn't take me to the theatre to see Chekhov when I was growing up – we went to see Francie and Josie once every five years. It might sound odd because I always seemed very arrogant but I was actually terrified. I wasted years fretting about it all, trying to do the right thing, being neurotic, but there was actually nothing to worry about."

The decision not to mope around in misery for the rest of his life, and to enjoy himself more, was made when he was 43, and marked the end of his Strictly Sinatra depression. The relaxed look suits him. In fact, it's hard to imagine Capaldi as anything other than he appears today – carefree, a little battered by life, but no more so than anyone else.

He has developed a "this is about to happen" approach when speaking about things, even though they might never happen at all. He has spent much of the last seven years on The Jacobite Slipper, a feature-length script he has written and plans to direct.

Ewan McGregor is reported to be the producer, after coming in on the project several years ago, and is down to play four different roles in the film. The plot revolves around the making of a fictional 1938 film about Bonnie Prince Charlie, on a studio set with painted glens, lace costumes and powdered wigs.

"One of the extras is a dead ringer for Bonnie Prince Charlie, who is an alcoholic and vanishes when the film goes into production," says Capaldi. "The star is replaced by the extra, without the extra ever knowing that he's been duped into this role."

And what stage is it at now? Has initial filming started? "No," he says. "It's basically nowhere." His laughter erupts, sweeps both of us up, stops dead. "If I start talking about the legal issues I'll just get more crappy letters," he says. "But the film has been endangered." Filming could start very soon, or in five years, or maybe never.

"What people don't get is that I don't care," he says. "If it doesn't happen then so what? It's only a film. I'd love to make it, but there's no point making a film unless I can have enough traction over it to fill it with my own creativity. I can't be arsed, you know, but it's taken me years to realise that."

He enjoys painting and drawing, which he does every day, following a conscious decision some time ago to reincorporate art into his life. He draws the storyboards for films that never get made, sometimes to tell the story explicitly, and sometimes to capture the "feel and atmosphere" of an idea. There are other things he could try – directing episodes of The Bill, being a strictly commercial television writer – but he's not hugely interested, regardless of financial necessity.

He still regards himself as an actor first and foremost, which raises a seemingly obvious question: why get involved in the process of writing films, and trying to breathe life into them, when they seem destined to die on the vine? "I'm creative," he says. "I can't relax unless I've got some project on the go. I'm somebody from art school, and art school during the punk era, when you just had a go at whatever came along."

Now that punk is dead, and he is 50, he is determined to get his kicks where he finds them. "I just consciously try to enjoy the good things that are happening," he says. "And if it ended tomorrow that would be fine." He smiles, reconsiders. A hint of Malcolm Tucker flashes across his face, as if another bodily possession is imminent.

"People talk such shit in interviews. There's no control, nobody's got any control. I can sit here and say I'll be doing The Jacobite Slipper, or another series of The Thick Of It, but then you get a phone call and somebody says, look at the papers tomorrow' and everything's fucked." He laughs, but only half convincingly. "There's always a cosmic sledgehammer just waiting to destroy all your plans."

First published in the Sunday Herald, 2008.